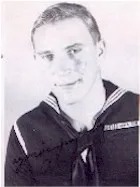

Albert Meier

Seaman First Class (Gunner striker)

Oral History

July 7, 2001

Herbert T. Hoover: This is an interview with Albert Meier, a crewmember of the battleship USS South Dakota, conducted by Herbert T. Hoover on July 7, 2001, at the Ramkota Hotel in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, during the reunion of the crew of the battleship. Would you say your name and where you are from?

Albert Meier: My name is Al Meier, and I’m from Edgewood, Washington, at the present time.

Hoover: We usually begin by asking how you happened to get in the Navy and on USS South Dakota.

Meier: I left South Dakota when I was about fifteen years old and moved to the state of Washington, went to work on a dairy there, had a brother that was in the Navy, and he got bombed at Guadalcanal and was missing in action. I couldn’t wait until I was seventeen so I could go get even with the Japs for getting my brother. So the day I was seventeen, I joined the Navy and went to Farragut, Idaho. As soon as I got out of there, they put me on USS

South Dakota. I was such a green farmboy at that time I thought the Navy had done it on purpose. But I soon found out they just needed another man swabbing the decks.

Hoover: You’re actually a native South Dakotan. Where did you grow up here?

Meier: Around Kimball, South Dakota.

Hoover: What took you out there?

Meier: If you remember back in the Thirties, I came from a family of seven kids, and my father had died when I was about a year and a half old, and my mother took care of seven kids on the farm during the Depression. We slowly starved out. One sister went to the state of Washington, and we kind of all followed.

Hoover: You were trained at Farragut. What do you remember about that?

Meier: I remember five-sixty-five. I can’t remember what our company commander’s name was, but he was a great guy. He taught us a lot. I remember it was hot, and we spent a lot of time out on that grinder in the middle of summer. I always say it was the best thing that ever happened to me that I got into the Navy because it taught me a lot of discipline. I learned a lot of discipline there, and I learned a lot of discipline on the ship. It was a good experience. I remember going from Tacoma to Farragut on a train, kind of like a cattle car, with wooden seats in it. Being a kid off the farm, it was quite an experience. I found the food really was quite good.

Hoover: That must have been really a moment for you, coming from South Dakota and getting on this huge ship. What did you think when you first saw USS South Dakota?

Meier: For a young kid, seventeen years old and hadn’t really been uptown very much, it was a huge ship. I just couldn’t imagine how they could make it out of steel and how it could float. It took me a long time to understand that. It was just mindboggling for a young kid. I couldn’t believe how fortunate I was, because everyone thought a lot of their home state, and to end up on the battleship South Dakota was just unbelievable.

Hoover: Where did you board it?

Meier: In Bremerton. It had been there for battle damage. I didn’t spend as many years on it as a lot of people, but I did get into–when we first went back out, we took the Philippines and got into some battles there, and of course Okinawa and Iwo Jima, and we got to go into Tokyo Bay.

Hoover: What was your rating–your specialty?

Meier: I was a seaman first class, but also I got what they called a gun striker. We were on the twenty millimeters, which was great for me because I was up there and I could see the action. Once in a while you’d get locked down below deck, with the firing and stuff going on, I didn’t enjoy that. I wanted to be up there where I could see. My battle station was right behind one of the sixteen-inch turrets. We had to be on our battle stations even when we were

bombarding, so every time they’d fire one of those, we’d bounce about eighteen inches off the deck. They gave us a couple pieces of cotton to put in our ears, so you can see why I have hearing aids to show for it. But young kids, we didn’t think it was going to bother us. I could have put in for a claim when it was time to get out of the Navy, but I was in such a hurry to get out of the Navy. I wanted to go home, and I wasn’t going to tell them anything, for fear they’d keep me another day or two.

Hoover: Take us through your memory of being a gunner.

Meier: We went from Bremerton to Pearl Harbor, which again was an experience. Being from South Dakota, I didn’t know much about the Hawaiian Islands. They brought Hilo Hattie on board for entertainment, and then we got to go ashore, so that was a whole new world for me. I didn’t realize there was such a thing as Hawaii. I thought that was pretty neat. We did some practicing, firing, on the way out to the war zone. It was a lot of noise, but I’ll never forget the first time when we actually got into battle and the Zeros were coming in, and all the guns opened up. It was such a noise, it was almost impossible for me to believe all this was happening. It just really scared me bad. But after the first one–of course it was my job at that time to load the ammunition onto the twenty millimeters–we had magazines. One person had

to load, and when we got through with that, you had to take it off and somebody else added another one. When I got onboard ship, they didn’t have enough bunks for everyone, so they told us, you’ll have to sleep wherever you can. So we used to sleep on the ready boxes–they were about six feet long, where they kept the ammunition. It was outside, so we’d lay on those, and

use life jackets for pillows. Every once in a while, we’d run into a rain squall. In the Pacific, when it opens up, it does. Before you could wake up and get away, you were soaking wet. You spend a lot of time sitting around and waiting; you aren’t fighting all the time. We did a lot of time swabbing the deck when we weren’t at our battle stations. We’d swab the deck and then go inside and sit down and maybe start playing cards, and the bos’n would say,

“You guys get out and swab that deck.” We didn’t say, “We just got through.” You went back out and swabbed the deck. That’s where I learned the discipline. You didn’t talk back; you did it. I wish some of my kids had that training.

Hoover: Of the two thousand men onboard that ship, how much of that society did you get to know?

Meier: We got to know most of the people in our own division. I was in the Ninth Division. Then you just try and find people from your home state and from your area, and some guys just kind of hooked up together. But you didn’t get to know the majority of them. I probably didn’t get as acquainted as someone that might have been twenty-five years old, being a seventeen-year-old kid, a lot of guys could have been my father. The fellows that had been on there four or five years, they just looked at us as some kids they brought on. So you kind of had to stay with your age group. But we always got along fine. We didn’t have any problems. Once in awhile, we’d go to Ulithe to go ashore when they were putting on supplies. We’d get two cans of beer, and that’s all it took to get you in a fighting mood. So we used to have our

ups and downs there.

Hoover: Did you have any trouble with seasickness?

Meier: No, I was very fortunate. I was on when they had the bad storms, around Okinawa with the typhoons, and it was rough. I never got seasick. It was part of our job, when we were refueling destroyers–the hose would go across and we used to pull it in with lines, we had to keep the hose up out of the water–pulling the lines in, and then we’d hit a big wave. It seemed like whenever there was a storm coming up, when they’d want to try and get some fuel on those destroyers to keep them afloat. I’ll never forget the time we did our best to refuel as many as we could, but it got so bad, the last two we couldn’t refuel, and we lost those. They capsized during the night. Those were fifty-foot waves. It was rough. I always say the real heroes of the war were the people that were on the destroyers. When we were refueling, they bad to be out there working, and they had to actually tie themselves to the ship with ropes. Waves would slap them up against the side, and they took

an awful beating. They were the real heroes in the war. We didn’t roll nearly as much. A lot of time you’d be tipped, where we’d be up three or four decks, and you’d look out, and you’d be looking into the ocean. But we didn’t ever worry about tipping over.

Hoover: What do you remember about the times the guns opened up and you were in battle? Were you worried?

Meier: I don’t think we ever really worried that they was going to sink us, or anything like that. We just didn’t think about that. I remember the first time all the guns opened up, and the next thing I realized, someone kicked me in the butt. I was standing there with my hands over my ears, and I’m supposed to be putting the ammunition on there. So the gunner kicked me and said get that ammunition on there. He even put me on report because I wasn’t doing my job. That was the only time it happened. But it really scared a young kid. That’s treason for not during your job during wartime. So I assure you, it never happened again.

Hoover: Did you fire the guns at all?

Meier: Towards the end, as we got into Iwo Jima and that area, then I was able to fire the twenty millimeters. Every so many shells they have a tracer, so as you’re firing, you would see those going out, so you know where your bullets are going. They would always go in a circle. You couldn’t shoot straight at anything. You could just kind of follow it and see hopefully you were shooting ahead so that the plane would come into you. They did start

using a little radar toward the end of the war, but it never worked as good as your own eyesight. Of course, you never knew for sure whether you shot a plane down or not, because there were so many people firing. Everybody said they did it. I can recall one time when we were under attack, and I could see the deck–we had wooden decks–and the Japanese was firing this gun, and the wood was just chipping up. It was headed right this way. You could

see the chips flying. But just before he got to us, evidently he ran out of ammunition. That probably scared me as much as anything.

Hoover: Now you were there at Iwo Jima. What was the South Dakota doing?

Meier: Our main job, of course, was to protect the carriers–to keep the planes away from the carriers, because they were trying to knock our carriers out. So we were on our battle stations most of the time. A lot of times we had rations, because they couldn’t let us go down to eat because you never knew when one of these planes were going to come. They did an awful lot of damage, those kamikaze planes. And then, of course, we bombarded Iwo Jima and Okinawa. That could go on for several hours, where we would get in close and bombard. That really didn’t bother us too much, except once in awhile we would come under attack, and then we had to stay at general quarters all that time. But the biggest part was being at the station

when those guns would go off, to bounce off the floor. There was a lot of heat, you know. When they fired, they belched a lot of fire. But it kept life interesting.

Hoover: Do you remember any particular shipmates?

Meier: I have a fellow here today from Marysville, Washington. Jim Johnson. We used to go on liberty together. After the war he came up to Washington to my hometown and visited me. A couple of others–John Lock, whom you interviewed, he was in my division. He was older, but he kind of looked after us young fellows. We lost track of most of our buddies that we used to go on liberty with. We were on there about eighteen months before we ever got off on liberty, so those were the fellows that we–as soon as I came into San Francisco, I got a thirtyday leave to go back to the state of Washington. I came back and the ship was in San Pedro. I caught it there, and we went through the Panama Canal. When we got to the East Coast, I got a discharge right away. I had enough points. I was supporting my mother at the same time, so that gave me enough points to get out. I didn’t really spend much time on the ship during peacetime. Out of twenty months in the Navy, eighteen months was overseas.

Hoover: You were on board when it went into Tokyo.

Meier: Oh, yes, in Tokyo Bay. That was another great feeling, going into Tokyo Bay. They had to put up a white flag every place they had a gun mplacement. They had dug them into the rock. We went in through the channel into Tokyo Bay, which took–if I remember right–a half day or so. But there was just one flag on top of another. Everywhere you looked, there was a white flag. If we would have ever had to go in there with a ship, it would have almost been impossible. And they couldn’t bomb them because they were dug into the hillside. So it was a blessing that we had the bomb because there would have been a lot of lives lost.

Hoover: That must have been an eerie feeling.

Meier: Oh, just to think that we’d have had to go in and try and take all those out before we’d ever won the war if they hadn’t given up. But it was a great feeling, because we were the first major ship to go into Tokyo Bay. We were the first ship that bombarded the Japanese homeland also.

Hoover: Where did you bombard, when you were bombarding the homeland?

Meier: The name of these cities I don’t recall, but it was the main steel mills. We were right off the coast. You didn’t see much, because we were fifteen miles out. They would just lob those shells over. We’d see all the smoke and everything burning. It made us feel good that we knew we had them on the run. But we still didn’t know how long they’d hold out. The Japanese were pretty smart people. One thing that amazed me–before I went in, you’d see

pictures in the paper of Japanese–they kind of made them look like animals. Then when I got out there and I saw their battleships and the things that they were doing, I said how can these dumb people–I thought we were going to go out there, and we’re so much smarter than they are–how can these dumb people do all these great things? I found out they weren’t what we’d been led to believe. They were smart people just like we were. Then, of course, we were in Tokyo Bay when they signed the peace treaty. I was one of the fellows that helped polish the brass. We had everything shipshape, because we really thought they were going to sign the peace treaty aboard the South Dakota. And then all at once somebody figured out, Truman is from Missouri. We were just far enough off–with field glasses we could watch the ceremony. And Nimitz was aboard–we were the flagship during the ceremony. So we were a pretty important part of it. But we were certainly ready for it. Waiting in the harbor before and after the ceremony–that was torturous because we

wanted to go home. The war was over. Then seeing all those ships leave Japan, and then coming into San Francisco. It happened to be a foggy day. But as we got to the Golden Gate, our band was playing, and other bands were playing, the people were lined up, everyone was screaming and ollering, whistles were blowing. Alcatraz had a sign on it, “Welcome home, boys.” It was probably the greatest feeling I ever had in my life. You can’t imagine what a great feeling that was, after almost two years at sea, and then come home to a celebration. And then get right off the ship and be able to–they told us we could–within reason–don’t kill anybody– but do anything you want on liberty tonight. Just have a good time, guys. And we did. It was a good experience for me.

Hoover: Did you have any idea to stay in the Navy?

Meier: No, no, I had a mother and a sister that was still going to school, and they needed some help to make a living, so I was anxious to get home and make a living, so I never gave it a second thought. As much as I thought the Navy was great, I was still glad to get out.

Hoover: What is your occupational life then, since you got out?

Meier: For a couple of years, I had different jobs. I finally ended up being a fireman in the city of Puyallup, Washington. We’d work one day and be off two. On our days off, I worked at a lumberyard. After I was there awhile, the interstate was just coming through, and the people that owned the lumberyard had a chance to sell it, so they wanted to close it down. The

manager asked me if I didn’t want to go in the lumber business. But I didn’t have any money and he didn’t have any money. I talked it over with my wife, and she said we’ll never get any place if we don’t take a chance. I borrowed money and he mortgaged his house, and we started up in a 16 x 20 cabin. Thirty-five years later–my partner had passed away–we ended up with seven lumberyards and a distribution center, and sold out to a large company, and did rather well. The fact that I’d come from South Dakota and only gone through the eighth grade, that was pretty good. I have a lot of relatives in South Dakota, by Kimball, so I come back here every year and go pheasant hunting. I give most of the credit for my being able to accomplish what I did

from the Navy and what it taught me. They taught me right from wrong. I think discipline was the best.

Hoover: Did you have any trouble getting over the experience when you got off the ship?

Meier: No, I don’t think so. At the lumberyard, we used to have lots of problems, but I could go home in the evening and forget about it. I think that’s what I did in the Navy. I just kind of wiped it out. We didn’t talk about it too much. Probably the worst experience I had was when the ammunition come aboard and it exploded in one of the turrets and killed several guys.

Hoover: Tell me about that.

Meier: We were at sea and were bringing ammunition across from the ammunition ship. These powder kegs, I guess they were about five or six foot tall and about maybe two and a half foot in diameter. Some way or another, coming across that line, they picked up electricity. They got them down in the ammunition hold, and one of them blew up. Immediately they had to shut off lots of hatches and so forth. I recall it was about eight sailors got killed in that. They had to close the hatches down. But that ship was so big–this happened

forward, and people who were aft didn’t even know it happened. We had to have services and bury them at sea. Some of the fellows that were on a long time before that, they had been hit with bombs and torpedoes and so forth, so they went through a lot more than I did. But Okinawa and Iwo Jima, we used to get the reports and we knew what was happening over there. And

getting all these kamikaze planes. We’d be not very far from these aircraft carriers, when these guys would make a hit. The thing that amazed me, how those aircraft carriers could burn. They would just burn and burn, for days. You knew what those people were going through. The Princeton, they sunk it, and we were right close by when it got hit. So we saw a lot of bad things happen, but fortunately not to us.

Hoover: Did you know they were kamikazes when you saw them?

Meier: Once you saw them coming down, you knew they were. We had them coming across our bow, and we were able to shoot them down. Mainly they were after the destroyers and the carriers, but every once in awhile they would decide to check us out. But it was the carriers they wanted, so we spent a lot of time protecting them. Thank god we weren’t the guys who

were on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, because those fellows going ashore there, they just took a terrible beating. So I was thankful, even if I didn’t have a bunk to sleep in for six months, it was better than being on the beaches.

Hoover: I thought on battleships there would be enough.

Meier: They build them probably for twenty five hundred sailors. They kept adding more guns. I think we had over three thousand. So you either had to wait for somebody to die off or–they didn’t transfer a lot of them at sea. You had to wait your turn.

Hoover: Did you ever see the skipper?

Meier: Oh, yeah, yeah. He used to come around once in awhile. And once in awhile we’d have an inspection. They were usually pretty nice guys. Although they didn’t come around and visit with you.

Hoover: Anything else?

Meier: No. Being a young kid, I don’t have the big war stories. The greatest thing, of course, was to think that I came from South Dakota and moved away and then they put me on the battleship South Dakota. That was great.

Transcribed by:

Diane Diekman

CAPT, USN (ret)

3 January 2014